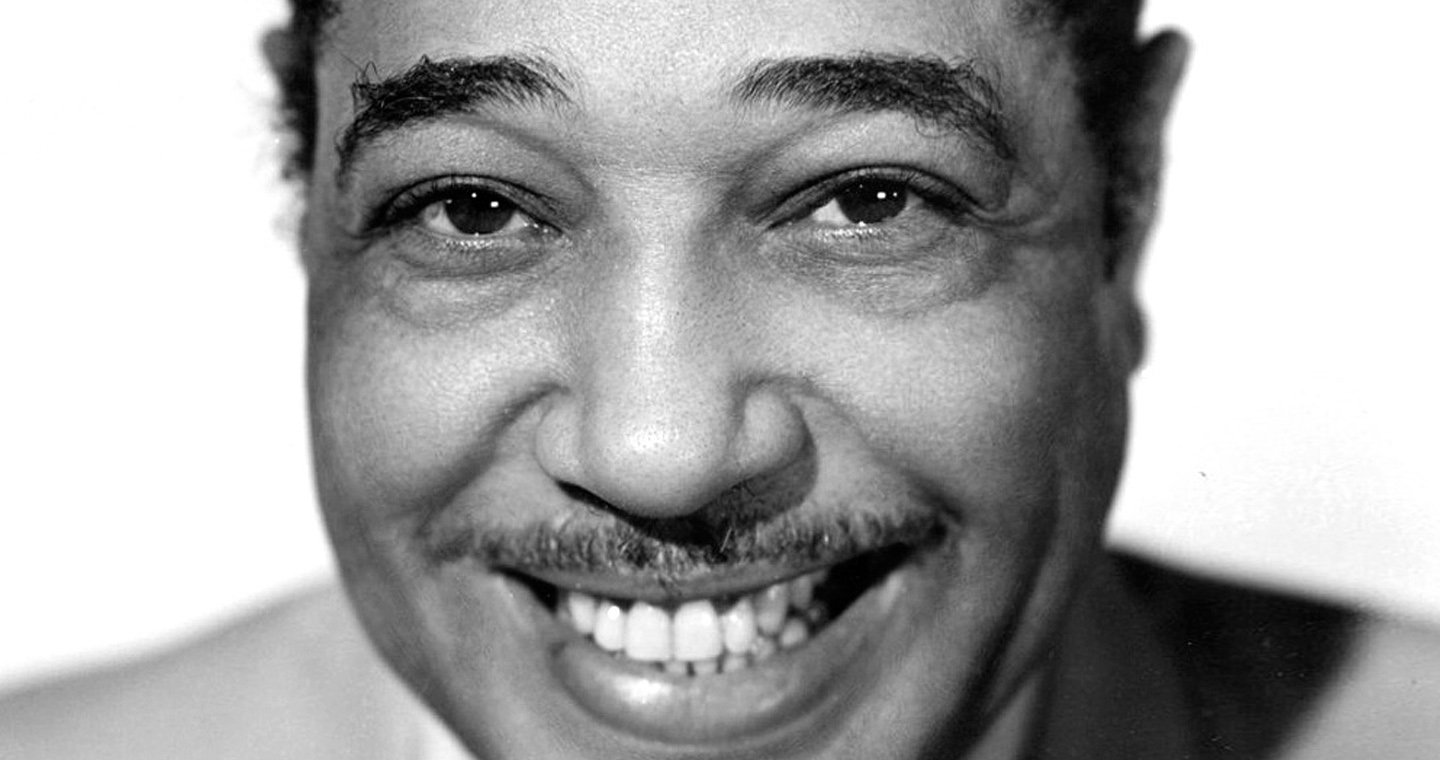

I’m not sure when I became quite so blasé about all this. There was once a time when I’d rigorously adhere to a set of eight questions and gently demand that any interview subject stay on mission. The only mission in question this morning is Apollo 11. Mark Steel is reciting a fabulously apocryphal revelation around something Neil Armstrong almost certainly did not say. It’s eating into my precious allotted time, but it is, inarguably, a great tall tale.

He’s doing a few of these interviews by Zoom today, but is happy taking life as it comes. “I've got the coffee and I've just had time to watch Chris Woakes get a wicket.” He’s just had a chap round to sniff about in his kitchen, where a mouse was seen last night. Steel doesn’t own a cat. “It would have done it a little bit cheaper,” he says with a hoot.

From mice in his house, we move on to talking about The Leopard in My House – a show, and accompanying book, exploring his experiences around a throat cancer diagnosis in 2023. “Yeah. A mouse is slightly less disruptive than the leopard.” It marks a slight change of direction for a performer who has been analysing everything on a macro level in recent years. He’s done shows about culture and communities, but now the hidden truths have become personal. He compares the period to being like a character in a strange play based on his life. “I do the shows, and try to do silly voices and make people laugh. But what has been different with this show is that quite a few people are affected by it. In a positive way.” He tells me he was astonished by the optimism shared by people in similar situations.

“Some people come up after the show, and want me to sign a book or have a chat with me. A lot have had cancer themselves, or their parents have… All of them say they're alright, even the ones who are in trouble. People can be immensely kind and generous. And then the hospital staff are, of course, both of those things.”

To succeed with such a deeply personal show, there has to be both an honesty and a sense of empathy for others’ experiences or expectations. “If all you've got to talk about is yourself, then you probably ought not to be doing a show. And if you can't relate it to other people, you probably ought to pay for a therapist instead.”

Many meet a cancer diagnosis with a curious levity. Those whom Steel met in hospitals seem to have been summoning cheer from a dark place. “People were funny… Deliberately funny. The chemotherapy room is one of the most positive and cheery rooms I've ever been in. There was one bloke who was just like some East End market trader. “Every time I saw him, he was like: ‘Alright Mark!’” Steel’s Estuary accent shifts up to purebred Cockernee. “He’d be saying: ‘They told me I needed chemo! I’ve got no bleeding hair to start with. That ain't going to trouble me, is it? Blimey, the things we do to get a day off work!’ And I think most people were some version of that.”

Away from the stand-up circuit, Steel has established himself as a broadcaster, finding critical acclaim for his BBC Radio 4 show Mark Steel’s in Town, which sees him deliver routines tailored to the location of each venue he visits. There’s also the BAFTA-nominated Mark Steel Lectures for BBC Two, which seek to deepen our knowledge of history’s most important figures. With a title that’s potentially too robust for the Corporation, his hit podcast, What The F*** Is Going On…?, has also been doing some tidy business.

The format is pretty simple. Get a fascinating person on (outings have welcomed Alexi Sayle, Rosie Holt and Dr Phillip Hammond), talk to them about their life and ask them to take on the near impossible task of quantifying current affairs.

“The guests aren’t just my heroes… I’m trying to ask people who may have some sort of answer. Or at least think they've got an answer. Just half an hour ago, I got a message saying Jeremy Corbyn wants to come on and do it.” Clearly, the former Leader of the Opposition heard the recent insightful Caroline Lucas episode and wants a bit of that sweet progressive cherry. Given current political manoeuvrings, it would make for an interesting booking.

“I quite like to talk to different people about what they think. There are millions of people asking: ‘What do we do about this? This isn't the world that we wanted in 2025!’ It is genuinely interesting.” You might be fooled into thinking there’s not much joy or entertainment in examining the seemingly random wheelie-bin fire that modern discourse has transformed into. But, like those experiences in the hospital wards, good-natured humour can spring from the unlikeliest corners.

“Some of it is so funny. You can’t stop it. But then, Farage is funny, isn't he? Regardless of how awful he is.” Steel suddenly lapses into a serviceable impression of the MP for Clacton, drawing out certain syllables and pausing at strange places, adding what some people might consider a tone of gravitas. “I was on a train and I heard several people in the carriage speaking in foreign languages. It made me feel rather uncomfortable…” He attempts to suppress a laugh, but ultimately fails. “That’s mental. If a foreign language makes you uncomfortable, it's like being one of these people who's scared of buttons or something…”

While some people might think Steel is mocking legitimate concerns, it does prompt questions about what the cut-off might be. Does the natural resolution for an intolerance to cultural differences see us all confined to our own village? Steel lapses back into his Farage voice. “Regional accents make me feel rather uncomfortable. Someone from Bristol was on the radio, and that is why I am introducing a bill to place an electric force-field around Somerset.”

While Farage might not be imminent for the podcast (it is a decent impression though), Steel tells me the naturally hilarious guests are the best. “There are many people like that. Miles Jupp… He is so funny. I was talking to him this time last year, at the cricket. The subject of shoplifting popped up, for some strange reason. I asked him if he’d ever done it, and without looking around, he went: ‘Yes, but always for the adrenaline rush, rather than the monetary gain.’ And then… he added that he has to steal services, rather than goods, because he was trying to declutter! I howled for about five minutes.”

Steel says his relationship with comedy hasn’t changed since his diagnosis. “I think I'm better placed to go: ‘Don't tell me I can't joke about this.’ I think if you're joking about cancer, when you haven't had it, then obviously you run the risk of someone saying you shouldn’t be doing that. I think it’s a mistake to assume if you make a joke about something, you don't really care about it. Often you care very much, or it might be your way of coping with it.”

A lot depends on quality, tone and context when judging if something is funny or simply cruel. He says you can see in people’s eyes what the intent is. When doing his In Town shows, the audience knows that he shares their affection for these communities.

He was in Newport once, and the show’s opening line was to announce how lovely he felt being in the town which was famed for industry, docks, mines, filth, grime and squalor. All the industry, docks and mines disappeared long ago, but somehow they kept the rest.

“I was going onstage, and suddenly thought: ‘I can't really say that, it’s horrible bollocks.’ But I did, and they all cheered. I always forget that people can see you're saying it with a twinkle. If you did think somewhere was a shithole, you could say exactly the same words and people would hate it.”

He feels fine these days, but admits there’s a strange sensation lingering after his cancer journey. It must have been a surreal situation, one which has left him wondering what it was all about. “It’s a bit like how Neil Armstrong must have felt when he got back from the Moon. It must have been all people wanted to talk to him about. To be fair, he didn't do a show called The Day I Went To The Moon. Well, he definitely did some chat shows and spoke to people about it, I guess.”

According to my extensive research, which was limited to a Neil Armstrong AI on the web, the astronaut did 20 - 25 chat shows and interviews in the months following the Apollo 11 mission, including The Johnny Carson show.

The same chatbot confirmed that Armstrong never whispered: “Good luck, Mr Gorsky” while walking upon the lunar surface. Steel tells me the reference was apparently directed at a childhood neighbour, who the astronaut overheard being informed that he’d only receive a certain sex act when “the kid next door walks on the Moon.”

“You know, the story may be apocryphal, but I've seen it in places that make me think it might be true,” he says, before starting to look it up on his computer. “Oh, it isn’t real… I'm shattered by that, to be honest! But for years, he was always being asked about Mr Gorsky. And going to the Moon.”

Mark Steel brings The Leopard In My House to Bromley’s Churchill Theatre on Fri 17 Oct, Ramsgate’s Granville Theatre on Fri 31 Oct, Theatre Royal Brighton on Sat 15 Nov and Canterbury’s Gulbenkian on Weds 3 Dec 2025, as part of his UK & Ireland tour. His podcast, What The F*** Is Going On?, is available via all respectable platforms.

Stuart Rolt

Featured What's On

Stay in the loop

Keep up to date with latest news, guides and events with the SALT newsletter.